Fractures & Trauma

Childhood Fractures

What Is a Fracture?

- Children are very energetic individuals and with increased activities, run the higher possibility they may take a fall or take a tumble. Although most falls are usually harmless, if a child impacts a surface with enough force the underlying bone may fracture

- A fracture is a break in a bone. Most bones in the body, given the correct circumstances, have the potential to break. Since bones provide the firm structure of a limb, a fracture may deform the limb and cause the associated muscle to no longer properly work leading to loss of function

- Most fractures follow a predictable manner that is related to the initial mechanism of injury. In addition to breaking, the ends of the fracture may move away from each other (displacement), bend at the site of the fracture (angulate), or rotate in relation to one another.

- Common locations of fracture include

- Hand (metacarpals or phalanges)

- Wrist (distal radius or ulna)

- Forearm (radial or ulnar shaft)

- Elbow (distal humerus and its condyles)

- Thigh (femoral shaft)

- Leg/shin (tibial shaft)

- Ankle (distal tibia or fibula)

- Foot (metatarsals or phalanges)

Who Is at Risk for Having a Fracture?

- Participating in competitive sports such as football, basketball, gymnastics, etc.

- Frequent falls or episodes of trauma

- Chronic stress or over use of a limb such as prolonged running

- Boy are more likely than girls to acquire a fracture

Does My Child's Fracture Heal the Same Way as a Fracture in an Adult?

- Until a child reaches skeletal maturity in his or her teenage years, a child is growing. Therefore, their bones have an enormous capacity to heal and do so much faster than adult bones

- A fracture in a child deserves more urgent attention than an adult because the healing process starts sooner and is more rapid. Therefore, a child should be evaluated by a pediatric orthopedic specialist within five to seven days, but preferably sooner

- The increased speed of healing also means a child requires less time in a cast than an adult

What are the Symptoms of a Fracture?

- Deformity of a limb

- Severe pain, tenderness, or inconsolable crying

- Swelling

- Abrupt onset of not being able to use a limb in its proper manner such as limping or refusing to use the dominant arm

- Some fractures may be very subtle and present only as chronic pain

How is a Fracture Diagnosed?

- A physical exam is necessary to ensure the skin, blood vessels, muscles, and nerves are intact as well as ruling out any other injuries to surrounding hard or soft tissues

- An injured limb should have x-rays (radiographs) taken of it at least once during the course of the child's treatment. This allows your doctor to assess the alignment of the fracture and optimize proper treatment. Even though x-rays do require exposure to radiation, the amount of exposure is negligible and less than that experienced at the dentist

- In some instances, an x-ray may not properly reflect the true nature of a bone especially when involving the growth plate of a child, thus your doctor may request a computed tomography scan (CT), ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Both MRI and ultrasound do not involve radiation. A CT scan is similar to a series of x-rays

How is a Fracture Treated?

- Treatment depends on the type of fracture, the degree of rotation/angulation/displacement, injury to surrounding structures, and the age of the child. In most cases a nonsurgical treatment plan is appropriate

- Nonsurgical treatment

- As long as the bone has not pierced the skin (called an open or compound fracture), injured a blood vessel, damaged a nerve, or significantly injured the growth plate, all attempts will be made to treat the fracture non-operatively.

- If a significant deformity of the limb exists, your doctor may attempt to manipulate the fracture with various degrees and direction of pressure or tension (called closed reduction) to achieve proper alignment of the bone fragments. This may require an injection of local anesthetic or sedation/anesthetic during the procedure

- A cast or a splint is applied to the affected limb to restrict movement at the fracture site (called immobilization) in order to ensure proper healing

- Surgical treatment

- Indications for surgery include:

- A bone piercing the overlying skin

- A fracture that easily moves or is at high risk for moving (termed unstable)

- Bone segments that are not properly aligned despite attempts at closed reduction

- Bones that have already begun to heal in an undesirable position

- Injury or threatening damage to surrounding blood vessels or nerves

- Significant damage to the bone's growth centers

- Indications for surgery include:

- During surgery, the physician opens the skin to realign the bones (termed open reduction) and may use pins, metal plates, and/or metal rods (termed internal fixation) to hold the bone in place till they have healed

- If a metal wire (also called a pin) is used to hold the bone in place, it is typically removed after healing. If a metal plate or rod is used it is typically left in place even after healing without any impairment of function. Indications to remove hardware are infection, pain, or breakage of the hardware

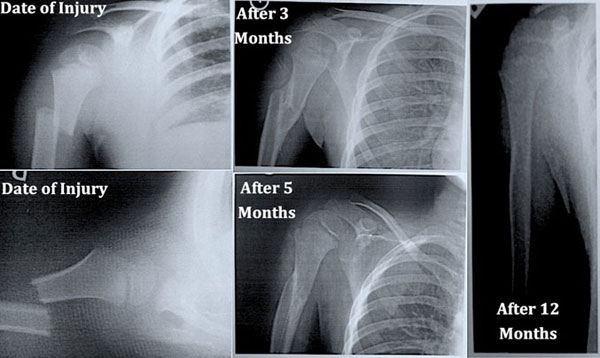

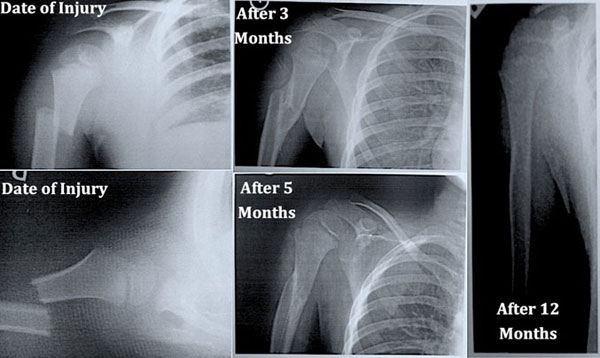

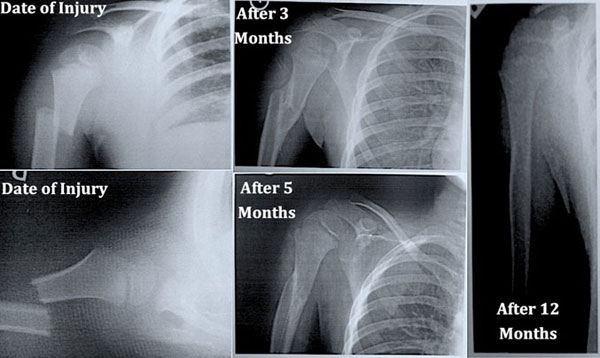

What is Remodeling?

- Remodeling is the process of changing bony architecture based on the stress patterns imposed across the bone

- This process primarily occurs in the skeletally immature patient (children)

- The bones of a young child have immense capability to remodel. Even grossly angulated bones have the ability to heal straight in a young child, even though some form of reduction is preferred

Click on the topics below to find out more from the Orthopedic connection website of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Growth Plate Fractures

Introduction

- Even though the bones of a child and adult are made of the same material, children are not "little adults". In order to grow, children have growth plates, which may be subject to fracture.

- Growth plate fractures require immediate attention because long-term consequences may arise, such as unequal or arrested growth in the affected limb

- Appropriate evaluation by an orthopedic surgeon experienced in pediatric orthopedic trauma will determine the nature of the growth plate injury, provide counseling about treatment options, and allow for long term follow ups to assess the outcome of the injuries.

Description

- The growth plate (physis) is an area of developing tissue near the ends of long bones, between the widened part of the shaft of the bone (the metaphysis) and the end of the bone (the epiphysis).

- The final length and, in some aspects, the shape of the mature bone is regulated by the growth plate

- Long bones do not grow from the center outwards. Instead, growth occurs at each end of the bone around the growth plate.

- The growth plate is the last portion of the bone to harden (ossify), which leaves it vulnerable to fracture. Because muscles and bones develop at different speeds, a child's bones may be weaker than the surrounding connective tissues (ligaments).

- Fractures can result from a single traumatic event, such as a fall or automobile accident, or from chronic stress and overuse.

- Most growth plate fractures occur in the long bones of the fingers (phalanges) and the outer bone of the forearm (radius). They are also common in the lower bones of the leg (the tibia and fibula).

- Children's bones heal faster than adult's bones which has two important consequences:

- First, proper treatment by a pediatric orthopedic specialist should be sought within five to seven days of the injury (or sooner) before the bones begin to heal. This is especially so if the bones require manipulation to improve alignment

- Second, the period of immobilization required for healing will not be as long as compared to an adult

- X-rays initially make the diagnosis of a growth plate fracture. Occasionally other diagnostic tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or ultrasound are necessary to evaluate the exact nature of the fracture

Risk Factors

- As long as a child is growing, he or she is at risk. Children that are nearing the end of their growth potential are especially vulnerable

- The risk in boys is twice that of girls

- One third of growth plate injuries occur during competitive sports such as football, basketball, or gymnastics

- Nearly 20% of growth plate injuries occur during recreational activities such as bicycle riding, sledding, skiing, or skateboarding

Treatment

- Growth plate fractures are classified depending on the degree of damage to the growth plate and surrounding bone

- Several classifications exist for growth plate fractures, but the Salter-Harris system is the most widely used system. This classification helps determine the treatment of the fracture

- Type I fractures - these fractures break through the growth plate only. In many cases no shifting of bone occurs thus these fractures may not be visible on x-ray.

- Fractures isolated to the growth plate heal well and usually do not require surgery

- Treatment is with cast immobilization

- Type II fractures - classified as a break in the shaft of the bone next to the growth plate (metaphysis) and growth plate.

- This is the most common type of growth plate fracture

- Surgery is usually not required and treatment consists of cast immobilization

- Type III fractures - defined as a fracture involving the end of the bone (epiphysis) and growth plate

- Type III fractures have the potential to arrest the activity of the growth plate

- Surgery with fixation by metal implants is necessary to ensure proper alignment of both the growth plate and the joint surface

- Type IV fractures - these fractures break through the bone shaft, growth plate, and end of bone

- Like type IV fractures, growth may be halted

- Surgery with fixation by metal implants is necessary to ensure proper alignment of both the growth plate and the joint surface

- Type V fractures - similar to type I fractures, only the growth plate is injured. Unlike type I fractures, the growth plate is crushed

- The majority of these fractures have arrested growth

- Surgery is necessary to correct the injury

- Growth plate fractures must be watched carefully to ensure proper long-term results.

- In some cases, a bony bridge will form that prevents the bone from getting longer or will cause a curve in the bone. Orthopedic surgeons are developing techniques that enable them to remove the bony bar and insert fat, cartilage, or other materials to prevent it from reforming.

- In other cases, the fracture actually stimulates growth so that the injured bone is longer than the uninjured bone.

- Regular follow-up visits to the doctor should continue for at least a year after the fracture. Complicated fractures (types IV and V) as well as fractures to the thighbone (femur) and shinbone (tibia) may need to be followed until the child reaches skeletal maturity.

Remodeling

- Remodeling of bone is the process of a change in bony architecture based on the stress patterns imposed across the bone

- This process primarily occurs in the skeletally immature patient (child)

- The bones of a young child have immense capability to remodel. Even grossly angulated bones have the ability to heal straight in a young child, even though some form of reduction is preferred

Click on the topics below to find out more from the Orthopedic connection website of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Cast Care

What Is a Cast and Why Does My Child Need One?

- An orthopedic cast is a hard plaster or fiberglass shell with an inner padded surface that surrounds an injured extremity thereby preventing movement and providing protection

- By preventing movement, the cast immobilizes the underlying broken bone or torn ligament in the proper position allowing proper healing to occur

- The duration the cast is used depends on the type of injury

How Can I Take Care of My Child with a Cast?

- Elevation of the affected limb for the first 24 hours significantly reduces the natural swelling that occurs after an injury. Swelling is normal in the initial phase of the injury, usually lasting one to three days. The limb should be placed above the level of the patient's heart ("High Five" Position for arm injuries) by using either pillows or supporting the limb. Moving the fingers or toes of the affected limb may also assist in reducing swelling.

- Pain relief in the form of Tylenol, Ibuprofen or medication prescribed by your physician should be continued for at least the first 48 hours after injury. Medication should be taken as directed on the medication bottle. Aspirin should not be given to children and adolescents

- Checking the skin for redness, swelling, bleeding, sores, or color changes around all the cast edges should be conducted every day. The opposite limb may be used as a reference to determine worsening swelling or color changes.

- Bathing the affected extremity with a cast should be avoided in most circumstances. Unless the patient has specifically asked for a waterproof cast, the cast should not get wet. Wet plaster can become soft and crumble. Wet padding under a fiberglass cast can cause skin irritation, rash formation, and underlying damage.

- A sponge bath is most desirable to avoid wetting the cast when the child needs bathing, but the cast should still be covered in several layers of towel or plastic bags to ensure it stays dry.

- A variety of manufactured "shower/water safe" cast covers are available, but no single one is perfect. In the event a cast becomes wet, dry the cast with a hair dryer on the cool setting.

- Waterproof casts are available at an additional cost not covered by insurance. These casts can be completely submerged in fresh water thus the child may bathe, shower, or swim. Salt water should be avoided. Not all fractures are suitable for this type of casts such as those applied immediately after surgery or surrounding the ankle or elbow. To make sure the cast stays clean, run warm soapy water through it as needed.

- Placing objects within the cast must be avoided. At no time should the child place rulers, paper, pencils, pens, etc. into the cast. Furthermore, powders or lotions should not be placed in the cast. This does not mean the child or his/her peers cannot draw on the cast.

- Itching under the cast can occur and may be bothersome, but under no circumstances should an object be placed under the cast. Scratching the underlying skin may cause injury and/or infection. Itching may be overcome by tapping on the cast, blowing cool air in to the cast with a hair dryer, or giving the child an antihistamine such as Benadryl (diphenhydramine) as directed on the medication bottle may be helpful. If itching becomes severe and/or persistent, please contact the orthopedic office.

- Walking on a leg with a cast may damage the cast and underlying bone. Do not let your child walk on a cast unless your doctor has provided approval and if so use of a cast shoe is beneficial to protect the cast

- Activities of daily living do not necessarily need to be restricted if your child has a cast. They may go to school and play. However, they must avoid activities that can lead to cast damage, reinjury, or wetting of the extremity. Examples of inappropriate activities include but are not limited to: bicycle riding, swimming, roughhousing, contact sports, skate boarding, etc.

- Cast odor is normal and not an indication to change the cast. Odor is common because the affected limb cannot be bathed. Under no circumstances should powder or perfume be applied on or in the cast

Is My Child's Cast Too Tight? Too Loose?

- A cast that is too tight may decrease circulation to the affected limb, damage underlying skin, and/or injure underlying nerves. The most common symptoms of a cast that is too tight are:

- A feeling of numbness, tingling, or increased pain

- The fingers or toes of the affected limb are a different color than the skin of the non-injured extremities (i.e. pale or blue)

- New swelling of fingers or toes

- Swelling is to be expected in the first 24‐72 hours after injury or surgery of the affected limb and may lead to the cast feeling tight. This is best treated with elevation of the affected extremity

- A cast can become too loose, especially after the initial bout of swelling subsides. A child should not be able to remove the cast or significantly move the affected limb under the cast. Being able to place one or two fingers under a cast is appropriate.

When Should My Child Be Seen Again?

- Children who need a cast will also need close follow up. The patient should be seen again usually within one to four weeks. Ask your doctor when to return if they have not specified.

- If you do not have an appointment for your child or unsure of when the appointment is please call the Orthopedic clinic or Office.

When Should I Call My Child's Healthcare Provider?

- Call IMMEDIATELY if:

- Your child feels numbness, tingling, or increased pain.

- The affected fingers and/or toes turn an abnormal color such as white or blue

- The fingers and/or toes become severely swollen.

- Your child has trouble moving the fingers and/or toes of the affected limb

- Pain under the cast becomes severe and pain medicines do not help.

- Any drainage comes through or out of the end of the cast.

- A bad odor comes from underneath the cast.

- You notice a stain or area of warmth on the cast.

- Your child develops a fever.

- The cast feels too loose or too tight.

- The cast becomes soft or breaks.

- You have a fiberglass cast that doesn't feel dry in 4 or 5 hours after getting it wet.

- The cast becomes significantly wet

Click on the topics below to find out more from the Orthopedic connection website of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.